🕓 Last Updated: February 23, 2024, 11:32 am (PH time)

The looming ICC warrant of arrest for Duterte lies in how a preliminary examination into a crime against humanity goes.

But for ICC to bring President Duterte into their custody is a delusional affair, wishful thinking, and a fancy imagination.

Almost 10 months past April 24, 2017, from the filing of communication, the International Criminal Court (ICC) Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda released a Statement, on Feb. 8, 2017, signifying to open a preliminary examination into the mass murder situation in the Philippines reportedly committed by then Davao City prosecutor now President Duterte.

If the case would be found admissible, then an ICC warrant of arrest for President Duterte would follow.

The ICC prosecutor will be undertaking an examination into the reported mass murder crime in the Philippines that has allegedly been committed since July 1, 2016—right after the day that President Duterte assumed office.

Of Duterte’s flibbertigibbety words

A prosecutor has all the resources to plant evidence. President Duterte in one of his public speeches is just that good at using innuendos—unfiltered. No-holds-barred.

By all means, prosecutors can make or break the course of building up a case—the horrific reality.

Propaganda instead of a legal opinion

Spokesperson Harry Roque opines that for the ICC to continue looking into the case may undermine the Philippine sovereignty as domestic courts are functioning.

He also maintains that the alleged deaths were a legitimate police exercise. Of course, the ICC prosecutor would never buy that line of argument—naivety.

Roque continues pointing out the principle of complementarity.

In the Preamble to the Rome Statute of the ICC, it goes:

The International Criminal Court is not a substitute for national courts. According to the Rome Statute, it is the duty of every State to exercise its criminal jurisdiction over those responsible for international crimes. The International Criminal Court can only intervene where a State is unable or unwilling genuinely to carry out the investigation and prosecute the perpetrators. (Emphases are mine.)

Although Roque’s defense seems absurd yet comforting, the Duterte administration still cannot make any complacency as to poor-mouth the decision of the ICC prosecutor to open a preliminary examination into the crime.

What is principle of complementarity?

The ICC Prosecutor’s “Policy Paper on Preliminary Examinations”[1] assesses the principle of complementarity based on an empirical question of whether or not the State Party (the Philippines, in this case) has been looking into the crime. Otherwise, the reported communication of the alleged crime committed is admissible.

The principle of complementarity doesn’t end up having domestic criminal courts functioning. It rather speaks of what the State Party has been doing about the crime to serve justice and prevent the culture of impunity.

As for the ICC to intervene, the Philippines must have been “unable or unwilling genuinely” to prosecute the perpetrators of the crime. Then, how does the principle of complementarity work so that the ICC can find substantial grounds qualifying the case admissible?

To quote the ICC Prosecutor’s “Policy Paper on Preliminary Examinations”, the following factors are considered:

(a) the proceedings were or are being undertaken for the purpose of shielding the person concerned from criminal responsibility for crimes within the ICC jurisdiction, (b) there has been an unjustified delay in the proceedings which in the circumstances is inconsistent with an intent to bring the person concerned to justice, and (c) the proceedings were or are not conducted independently or impartially and in a manner consistent with an intent to bring the person concerned to justice, (c) whether, due to a total or substantial collapse or unavailability of its national judicial system, the State is unable to collect the necessary evidence and testimony, unable to obtain the accused, or is otherwise unable to carry out its proceedings.

Now, has the Duterte administration been doing otherwise so that justice to the victims of summary killings allegedly committed since July 1, 2016, be served even if it takes longer than the distance measured in light years? This must be the substantial argument the Duterte administration would have been telling us.

Mass murder crime established before Duterte became president

The alleged mass murder crime has been the “culture of impunity” since his Davao time. That is the 77-page communication that was submitted by Atty. Jude Josue Sabio to the ICC prosecutor would try to tell the world. It underpins the mass murder crime (considered a crime against humanity) allegedly committed by President Duterte way back when the President was still the Davao City mayor. It tries to link Duterte to the notorious Davao Death Squad.

The communication also attempts to explain that President Duterte reportedly has been doing the same crime since he assumed office on June 30, 2016.

Would the allegations contained in the communication hold water now that the ICC prosecutor opens the preliminary examination into the crime?

Somehow, it may provide the ICC prosecutor with a clear picture that President Duterte is capable of doing so and that there may be a systematic approach to committing the crime now that he became president.

Time frame of crimes under ICC jurisdiction

The Philippines ratified the Rome Statute of the ICC on Aug. 30, 2011, and the entry into force was on Nov. 1, 2011. This means, according to the Rome Statute, that only crimes committed after the entry into force (in the Philippines’ case, 1 November 2011 is the date of entry into force) will the ICC has jurisdiction.

This means that all crimes committed by President Duterte, if there are, from Nov. 2, 2011, up to the present, may be given consideration to look into.

However, the ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda in her Feb. 8, 2018 statement specifically stated that only crimes committed from July 1, 2016, onwards will be under the preliminary examination. Sounds absurd?

Fatou Bensouda also stresses that no provision in the Rome Statute that sets a specific time or period for the termination of a preliminary examination.

Now, this is advantageous to the Philippines. Why? Sounds like a big deal?

This way, state-sponsored crimes, if there are, maybe curbed, controlled, or minimized if not totally be stopped. Unless the other side of politics rides for it by staging events using sacrificial lambs to hold the Duterte administration accountable for the crimes committed.

This way, the government must heavily rely on its intelligence-gathering discipline.

But do we have these sorts of intelligence and how’s the loyalty of these people?

A looming scenario: ICC warrant of arrest for Duterte

While the ICC warrant of arrest for Duterte could be wishful thinking for some but horrible anticipation for others, President Duterte “has been there, done that” when he was a city prosecutor. He may have been anticipating the worst to come.

If the ICC prosecutor finds the case admissible after substantiating the grounds on issues of jurisdiction and complementarity and in the interest of justice, it will endorse the case for an investigation.

After substantiating the gravity of the crime committed, President Duterte may be arrested.

Ineffective police power; subjects can be at-large

The ICC has no police power or forces to track down President Duterte, if in case, and arrest him.

In 2015, the ICC issued two warrants of arrest against Sudan President Omar al-Bashir for the crime of genocide. The ICC failed to bring President Omar al-Bashir into their custody.[2]

Joseph Kony and Vincent Otti both from Uganda for a crime against humanity have remained at large since 2005 based on an April 2018 updated Case Information Sheet.[3]

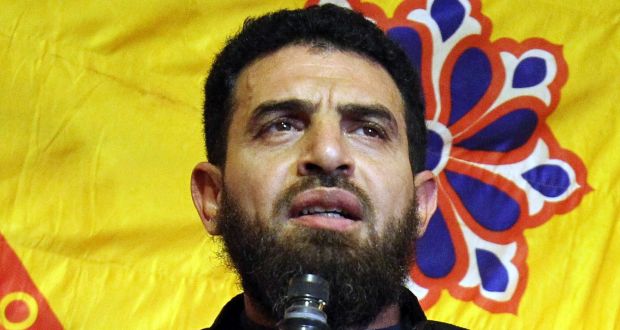

In 2017, the ICC issued a warrant of arrest on 15 August 2017 against Mahmoud Mustafa Busyf al-Werfalli for the crime of murder as a war crime reportedly committed in Libya. Mahmoud al-Werfalli also remains at large based on a July 2018 Case Information Sheet.[4]

Based on the reported cases of State Parties’ non-cooperation with the ICC in terms of a warrant of arrest compliance, the Republic of Djibouti and the Republic of Uganda (both are State Parties to the Rome Statute) failed to comply with the request of the ICC to arrest Sudan President Omar al-Bashir in 2016.[5]

The Republic of Kenya, also in 2016, failed to comply with the cooperation provision of State Parties[6]. In 2015, the Republic of South Africa failed to execute the arrest warrant against Sudan President al-Bashir when he attended the 25th African Union Summit.[7]

In addition to State Parties believed to refuse and not cooperate with the ICC are Chad, the Central African Republic, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo which failed to execute the arrest request of the ICC against Hussein and al-Bashir.[8]

In other words, ICC has ineffective police power.

ICC warrant of arrest for Duterte be likely ignored

While President Duterte challenges the ICC prosecutor to shoot him rather[9], it cannot be set aside that there will only be two things: (1) either to abide by a decision of the ICC, (2) or to order the national police and the military to ignore ICC warrant of arrest for Duterte and face international retaliation.

Notable powerful countries like the United States, China, India, Israel, Egypt, Turkey, Iran, and Russia oppose the Rome Statute, and although some of them signed it but have never ratified it, so far.

Apparently, the ICC warrant of arrest for Duterte is a fancy imagination after all. And highly likely for President Duterte, himself, ICC is only wasting its time, full stop. President Duterte has China on one hand and Russia or India and the United States on the other hand. Then, why he should worry about international retaliation?

In hindsight, President Duterte’s federalism isn’t dead yet. He has also all the possible machinery to stage conflict or worst terrorism to put the entire country into fear. He could make all lies true by telling a lie again, again, and again. How he played his game so well is history’s part to teach us and learn from it. ▲

____________________________

[1] “Policy Paper on Preliminary Examinations”, 2013.

[2] Darfur, Sudan Investigation, 2005.

[3] Kony et al. Case, 2005.

[4] The Prosecutor v. Mahmoud Mustafa Busyf al-Werfalli, 2017.

[5] “Report of the Bureau on Non-Cooperation”. 15th Session, The Hague, 16–24 November 2016.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “Report of the Bureau on Non-Cooperation”. 14th Session, The Hague, 18–26 November 2015.

[8] “Report of the Bureau on Non-Cooperation”. 13th Session, New York, 8–7 December 2014.

[9] “Shoot Me, Don’t Jail Me, Philippines’ Duterte Tells Hague Court Prosecutor“. Reuters Staff, February 9, 2018, 9:27 PM.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated organization, employer, or institution. The author bears sole responsibility for the content.

📩 Subscribe to The Philippine Pundit

Stay updated with the latest news, insights, and stories. Join our mailing list today!

Regel Javines is the independent voice behind the Philippine Pundit. With roots in grassroots work and government service—from open-source research analysis with the Philippine Air Force and news desk duties at The Manila Times, to development and congressional assistance work at Congress—he brings unique insights shaped by philosophy, justice, and lived experience. His mission: to give voice to the unheard and raise questions that stir the soul.