Table of Contents

Overview

Criticisms against the Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 10 can be likened to an avarice of extreme interest in something.

Slavery. Not only is it acquiescence but also recalcitrance. As one becomes more knowledgeable by any means possible in acquiring knowledge, one becomes more subservient to what one is most interested in. Be it (interest) serves the widest array of population in society or works only to the few, influential organisms in a specific niche, it still boils down to a despicably abject slavery. That is, either enslaved by one’s misplaced concern of being or an utterly desperate blunder and misconception about the diversity of major drivers of social change.

This unorthodox characterization of slavery fits the modern and modest definition of allegiance, in general, yet it always goes back to the etymological concept and nonconformist interpretation of slavery that is servility by conquest, which is also equitably meant in these modern days as fanaticism.

What does it mean?

Ordinarily, it is indispensable for people to look after their daily survival. They become enslaved by this concept of survival of the fittest, which was famously coined by British naturalist Charles Darwin in his 1869, On the Origin of Species. It correlatively means that people must tend to adapt to their environment, otherwise, they would be left behind or worse dead.

However, people are social beings, as well. As entities in a social being concept, people tend to compete for social belongingness as a human nature. Social psychologist Roy Baumeister and psychology and neuroscience professor Mark Leary firmly asserted this type of human needs as what they found out over their lifelong studies.

Summarizing these few lines of the overview leads to this one thought: People tend to attack their perceived enemies as they become threats to their concern of being which they are desperately enslaved of. An example of this servile behavior is fanaticism. And those who attack the propriety and legitimacy of the Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 10 appear to have suffered a deficit in understanding the critical concept of functions of leadership, lest they look at it as an affront to what concerns they are enslaved by.

What is the 2011 Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 10?

The Session 13th Journal of the Senate of the Philippines, 15th Congress, 2nd regular session on August 24, 2011, provides context on the creation and adoption of the Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 10.

During the roll call of the secretary of the Senate, 18 senators were present enough to reach a quorum. However, senators Alan Cayetano, Escudero, and Trillanes arrived after the roll call, while senators Legarda and Pangilinan were on an “official mission,” the session 13th Journal of the Senate wrote.

The following are 21 senators who were present during the introduction of the Senate Concurrent Resolution No.10 and reportedly had no objections to the resolution:

- Angara, E. J.

- Arroyo, J. P.

- Cayetano, A. P.

- Cayetano, P. S.

- Defensor-Santiago, M.

- Drilon, F. M.

- Ejercito-Estrada, J.

- Enrile, J. P.

- Escudero, F. G.

- Guingona III, T. L.

- Honasan, G. B.

- Lacson, P. M. (sponsor)

- Lapid, M. L.

- Marcos Jr., F. R.

- Osmeña III, S. R.

- Pimentel III, A. K.

- Recto, R. G.

- Revilla Jr., R. B.

- Sotto III, V. C.

- Trillanes IV, A. F.

- Villar, M.

Sen. Lacson, as the sponsor of the resolution, reiterated the constitutionally formed three coequal branches of the government: the Executive, the Judiciary, and the Legislative. He also reiterated that one of the important constitutional powers of Congress is the power of the purse. As necessary as it is, Congress enjoys fiscal autonomy besides institutional autonomy.

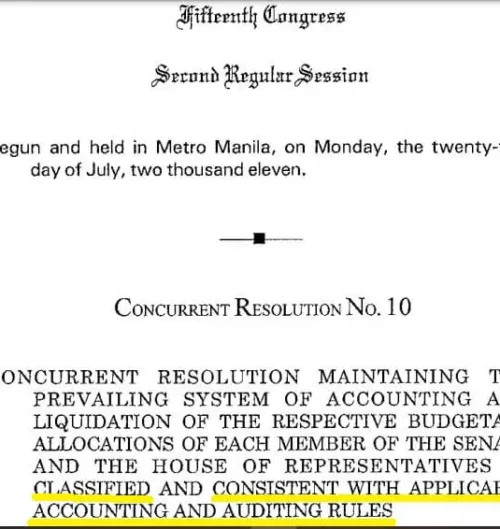

The Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 10, which was adopted unanimously in 2011, maintains that the prevailing system of accounting and liquidation of the budgetary allocations of members of Congress is “classified and consistent with applicable accounting and auditing rules,” the resolution provided for.

Why it was created and adopted?

Relatively, to enjoy the Congress its fiscal autonomy, the resolution must maintained. More significantly, by creating and adopting the resolution, Sen. Lacson emphasized that “it is an assertion of Congress of its powers and rights as a constitutional body.”

Moreover, Sen. Lacson explained how fiscal autonomy is granted in the Congress.

- By a constitutional provision in Article VI, Section 25(5) that provides, “the President of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives may, by law, be authorized to augment any item in the General Appropriations Law for their respective offices from savings in other items of their respective appropriations.”

- By a specific law provision under the general provisions of the General Appropriations Act that includes, “its inclusion in the enumeration of government entities possessing fiscal autonomy,” proving that “even the Executive Department recognizes Congress’ fiscal autonomy.”

Furthermore, Sen. Lacson pointed out:

The delicate nature of their duties as legislators calls for a system of liquidation by way of certification containing an itemized list on the manner the amounts allocated to each legislator were utilized or expended in the performance of their legislative functions, a system long recognized by the Commission on Audit and which in itself is a recognition by COA that Congress, like any constitutional body, enjoys fiscal autonomy. (Added emphases are mine.)

Is it prudent, legitimate, and legal?

By looking through the lens of suitability, propriety, and fitness to the nature of functions and degree and extent of work of legislators that the adopted resolution created to serve for that purposes, the adoption of the Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 10 has a reasonable doubt. Hence, it is prudent and legitimate.

Furthermore, it is legitimate as it can possibly facilitate smoothly in most critical operations of Congress. As Sen. Lacson emphasized:

It is also incumbent upon the Commission [Commission on Audit] to understand that to impose a more rigid requirement on Congress will be too burdensome that it may hamper Members of Congress in performing their legislative duties. (Added emphases are mine.)

Additionally, Rep. Edcel Lagman, in his manifestation on fiscal autonomy, opined that “the Congress is not prohibited from adopting a policy of equal fiscal autonomy… .”

Significantly, the Supreme Court (SC), in Bengzon vs. Drilon, defined fiscal autonomy as freedom from outside control. The SC furthered to define the scope and extent of fiscal autonomy in the following words:

As envisioned in the Constitution, the fiscal autonomy enjoyed by the Judiciary, the Civil Service Commission, the Commission on Audit, the Commission on Elections and the Office of the Ombudsman contemplates a guarantee of full flexibility to allocate and utilize their resources with the wisdom and dispatch that their needs require. (Added emphasis is mine.)

Moreover, reiterated in CHR Employees’ Association vs. CHR, the 1998 Joint Resolution No. 49 of the Constitutional Fiscal Autonomy Group defined fiscal autonomy, as follows:

Fiscal Autonomy shall mean independence or freedom regarding financial matters from outside control and is characterized by self-direction or self-determination. It does not mean mere automatic and regular release of approved appropriations to agencies vested with such power in a very real sense, the fiscal autonomy contemplated in the constitution is enjoyed even before and, with more reasons, after the release of the appropriations. Fiscal autonomy encompasses, among others, budget preparation and implementation, flexibility in fund utilization of approved appropriations, use of savings and disposition of receipts. (Added emphases are mine.)

Finally, is it legal?

In the absence of a specific law to apply the legal basis of the Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 10 to an expected level critics against it may suffice to understand it much better and clearer, and since this resolution revolves around the assertion of fiscal autonomy, a more relevant and encompassing law, the General Appropriations Act of 1998 or the R.A. 8522 provides special provisions applicable to all constitutional offices enjoying fiscal autonomy.

Conclusion

The Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 10 revolves around the assertion of fiscal autonomy that Congress, like any other constitutional body, must enjoy the same. Thus, it is legitimate by a reasonable doubt and by law.

Although the concept of fiscal autonomy may likely give birth to abuse of this power such as spending the allocated budget in a manner that is incomprehensible for anyone intelligent enough to understand overspending and extravagance on the use of public funds such as spending a Php125-million confidential funds in just 11 days. Such indulgence is worth a public clamor.

Yet, die-hard supporters, Filipino citizens at that, could even have the gall to protect their politician to the extent of going absurdly by criticizing the Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 10 as “legalized corruption” and worse “organized plunder”—a classic claim that is borne out of despicably abject slavery—equitably meant as fanaticism in these modern days.

Meanwhile, the Philippine Star wrote that the Commission on Audit on September 25, 2023, confirmed the controversial Php125-million spending of this humongous amount of confidential funds for just 11 days by the Office of Vice President Sara Duterte, who is also the secretary of the Department of Education.

Nobody could ever possibly imagine how Php125 million amount be spent in just 11 days. This issue, despite the flexibility and unimaginable extent of freedom that fiscal autonomy may entail, is worth investigating, rather than criticizing the resolution out of lack of a desperate counteraction. ▲

For supplementary, here is my LIVE talk discussing the 2011 Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 10.

References:

Bengzon vs. Drilon (G.R. No. 103524, April 15, 1992)

CHR Employees’ Association vs. CHR (G.R. No. 155336, July 21, 2006)

Journal of the Senate of the Philippines (15th Congress Second Regular Session, Session 13, August 24, 2011)

Since 2011, Regel Javines has been writing online, sharing news and analysis on a range of noteworthy and urgent social issues. He completed his bachelor’s degree in office administration at the Polytechnic University of the Philippines (PUP)—Taguig Campus, where he also served as editor-in-chief of the official school newspaper. See Regel’s published articles here.