🕓 Last Updated: June 4, 2025, 12:26 am (PH time)

To be born poor is not a choice. But to remain uncritical of the conditions that keep us poor—that is the choice we must confront.

Regel Javines, Founder & Editor-Publisher of The Philippine Pundit

This memoir by Regel Javines details his transformative journey as an iskolar ng bayan in PUP (2003–2007), shedding light on student activism, systemic poverty, and the ideological currents that shaped campus life. (Continue reading Part 2)

Surviving the “Sintang Paaralan”

As an iskolar ng bayan, I was one among thousands in the halls of the Polytechnic University of the Philippines (PUP), the largest state university in the country by student population. But more than just a name etched on a university ID, being an iskolar ng bayan was a badge of both pride and burden—a lived condition that demanded resilience, awareness, and radical questioning.

PUP has long stood as “the poor man’s university“—where dreams deferred by poverty find footing, where tuition fees remain at an unimaginable ₱12 per unit, and where students organize, resist, and rise. In my time, we fought hard to preserve that affordability. The 12-peso tuition did not come by default; it came by defiance.

Yet for the rest of society, the heroism of student activists is often unseen. The battles fought within our campuses—to freeze tuition hikes, to resist militarization, to demand dignity—are rarely heard outside the four corners of our classrooms.

But for me, those classrooms were not just spaces of instruction—they were battlegrounds of ideology, shaped by the influence of Marxist-Leninist-Maoist (MLM) thought that permeated student consciousness. Campus activism was not a mere accessory; it was the heartbeat of the university.

A Brief History of PUP

Founded in 1904 as the Manila Business School (MBS), PUP went through several name changes—becoming the Philippine School of Commerce (PSC) in 1908, the Philippine College of Commerce (PCC) in 1952, and finally, the Polytechnic University of the Philippines in 1978.

But the vision remained: to serve the marginalized, to equip the youth for public service and entrepreneurship, and to uphold education as a public good.

Today, students in PUP are called iskolar ng bayan—a powerful label reflecting the university’s mission to educate the underprivileged. Our tuition was subsidized, not by charity, but by a social contract: the government, funded by public taxes, owed education to its people.

From Leyte to the Metro: A Journey of Unknowing

I graduated valedictorian in both elementary and high school in a remote barangay in Cahagnaan, Matalom, Leyte. But academic awards didn’t equate to access or awareness. When I arrived in Manila in May 2000, I didn’t even know what the University of the Philippines College Admission Test (UPCAT) meant.

With dreams of a chemical engineering scholarship at the Technological Institute of the Philippines (TIP), I traveled across islands. Stranded in Samar. Sleepless in Tondo. Turned away at the University of the Philippines because I didn’t know I needed to take the UPCAT. The admissions lady just smiled. That was the day I understood that poverty doesn’t just deny opportunity—it blinds you to its very existence.

I worked. I survived. Dishwasher. Janitor. Waiter. Fast food crew. I embraced the working class in its rawest form before ever setting foot in a college classroom. Then, by late 2002, while working part-time at Wendy’s in SM Bicutan, I decided to take a chance on the Polytechnic University of the Philippines College Entrance Test (PUPCET).

Taking the PUPCET: First Steps Toward Becoming an Iskolar ng Bayan

I entered the PUP-Taguig Campus in 2003 with no test preparation, no clear course preference, and no illusions. Just a lingering hope—and a quiet resolve.

PUPCET was a test not just of mental ability but of endurance. Each subject competency was time-pressured. I distinctly recall the exam room in the Engineering Building. My proctor was Prof. Usona, later my scholarship head and math idol. I tried to solve every problem with discipline, even the ones I wasn’t sure I could answer on time.

I passed. But passing wasn’t everything. There were more steps—interviews, medical checkups, and enrollment. And questions. Questions that haunted me:

Why pursue education when education itself is in crisis? Why chase degrees when society exploits the degreed? Why follow paths paved by systems built to divide?

These weren’t rhetorical musings. They were the early stirrings of a radical awakening.

On Being “Broke as Shit” Yet Educated

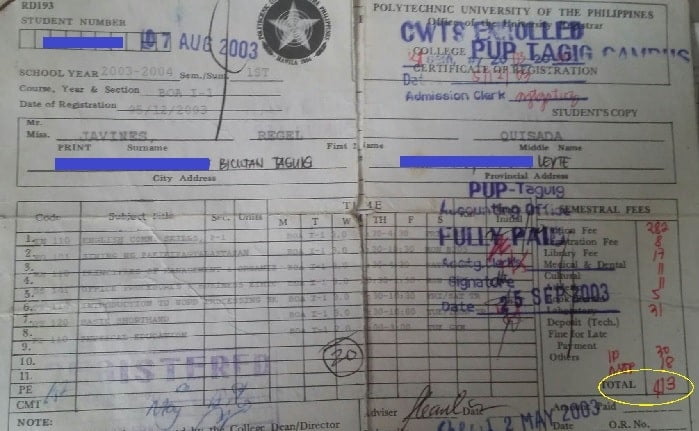

With less than ₱500 in my pocket, I enrolled full-time for my first semester. My total tuition and fees amounted to ₱413. That’s not a typo. That’s the cost of four years of formal university education for a young man who once worked as a janitor and couldn’t afford a book.

But what PUP saved in tuition, it paid for in sacrifice. My days were split—working fast food shifts while squeezing in classes, all while pretending that everything was fine. I didn’t even bother declaring I was valedictorian in high school. I saw no point. In PUP, merit was eclipsed by survival.

The University as Battleground: Where Activism and Ideology Converge

PUP has long been an epicenter of activism. From rallying against tuition increases to organizing for national issues, student activism here is not an extracurricular activity—it’s institutional memory.

The legal framework upholds this. Article XIV, Section 5(5) of the 1987 Philippine Constitution mandates the State to assign the highest budgetary priority to education. But we knew better. In PUP, we knew that laws don’t enforce themselves—activism does.

The ideological root of this resistance was clear: Marxist-Leninist-Maoist thought. This revolutionary socialist lens helped many of us understand the structure of exploitation, the illusion of democracy, and the role of education in perpetuating or dismantling systemic inequality.

Not everyone embraced MLM ideology. But for many of us, it was the only language that made sense of our condition—our poverty, our labor, our rage.

PUP: A Microcosm of the Philippine Struggle

PUP is not your typical university. It is a living contradiction: a sanctuary for the poor but also a pressure cooker for the politicized. It offers access but not always direction. It breeds both fear and fire.

Inside PUP, you meet students who slept on train benches, who protested in the morning, and who worked night shifts afterward. You see, lion cubs one semester become roaring revolutionaries the next. PUP is where your worldview is either broken or built—or both.

And every iskolar ng bayan you meet teaches you something. Every story is a theory in practice. Every hunger pang is a call to action.

A Living Revolution in a Dying System

When President Rodrigo Duterte signed the Universal Access to Quality Tertiary Education Act (RA 10931) in 2017, making tuition and other fees free in all state universities and colleges, it was a monumental win. But that victory was written first in the sweat and sacrifice of countless student activists.

We fought for that law before it was popular. We rallied before it was legal. We believed before it was possible.

Closing Reflection

To be iskolar ng bayan in PUP is to live within contradictions—between scarcity and knowledge, between ideology and survival, and between hope and struggle.

This memoir is not just a personal account. It is a testimony to how state education becomes a site of resistance, how consciousness is born not in comfort but in crisis, and how poverty, when politicized, becomes power. ▲▼ (Continue reading Part 2)

SEO Keywords: iskolar ng bayan, PUP student activism, Marxist-Leninist-Maoist ideology, PUPCET experience, Polytechnic University of the Philippines, poor man’s university, student activism in the Philippines, free college tuition law

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated organization, employer, or institution. The author bears sole responsibility for the content.

📩 Subscribe to The Philippine Pundit

Stay updated with the latest news, insights, and stories. Join our mailing list today!

Regel Javines is the independent voice behind the Philippine Pundit. With roots in grassroots work and government service—from open-source research analysis with the Philippine Air Force and news desk duties at The Manila Times, to development and congressional assistance work at Congress—he brings unique insights shaped by philosophy, justice, and lived experience. His mission: to give voice to the unheard and raise questions that stir the soul.